A VoicePrint Case Study

AlmostthefirstthingInoticedaboutGrahamwashowveryrapidlyhespoke.

Graham is a rather specialised sort of medical scientist, but he does not speak with the dry, measured diction of the stereotypical clinician. He talks brightly, with colour, energy and enthusiasm.

What also struck me in that first meeting was that Graham seemed so open-minded, ready and receptive for the coaching that his employer had decided he needed. This was an encouraging surprise, because it’s not easy to accept the feedback that you need lessons in anger management. It’s especially difficult to accept, if you’re already in a senior role.

What was not a surprise was that Graham seemed to lack self-awareness. While he acknowledged that he could ‘lose it sometimes’ and sound angry, and saw that this could have a negative effect on working relationships, he found it impossible to identify what triggered his occasional outbursts. He even found it difficult to describe himself in anything other than the most literal terms.

At the same time I found myself unexpectedly tired at the end of that first session. Graham talked fast and he talked a lot, about where he worked, his role, the challenges that the business faced and the things that he had to do. He was like a Rocket Man.

The proposition that I decided to work with was that Graham was a man in too much of a hurry. As a result, he was blind and deaf to the impact that he might be having on others until after the damage had been done. The first priority was to teach him to slow down, to learn to be in the moment and to recover the ‘presence of mind’ to be attentive to what was happening as it was happening.

I showed him how to do this by focusing on his breathing. Breathing is ordinarily so automatic that, if we take the unusual step of focusing our attention on taking slow, deep breaths, it has the effect of squeezing out the other thoughts that are clamouring for our attention. The exercise did not come easily, but that was a useful insight in itself. Graham felt his natural impatience, as he tried to focus on his breathing, and found other thoughts and preoccupations crowding back in. He found the breathing exercises strange and awkward, but at the same time calming and energising.

We then turned our attention back to his outbursts and introduced him to a number of techniques. These enabled him both to recognise and interrupt his growing impatience before it escalated out of control and also to discharge safely any deeper, pent-up concerns. Like the good scientist that he is, he was simultaneously somewhat sceptical and willing to experiment.

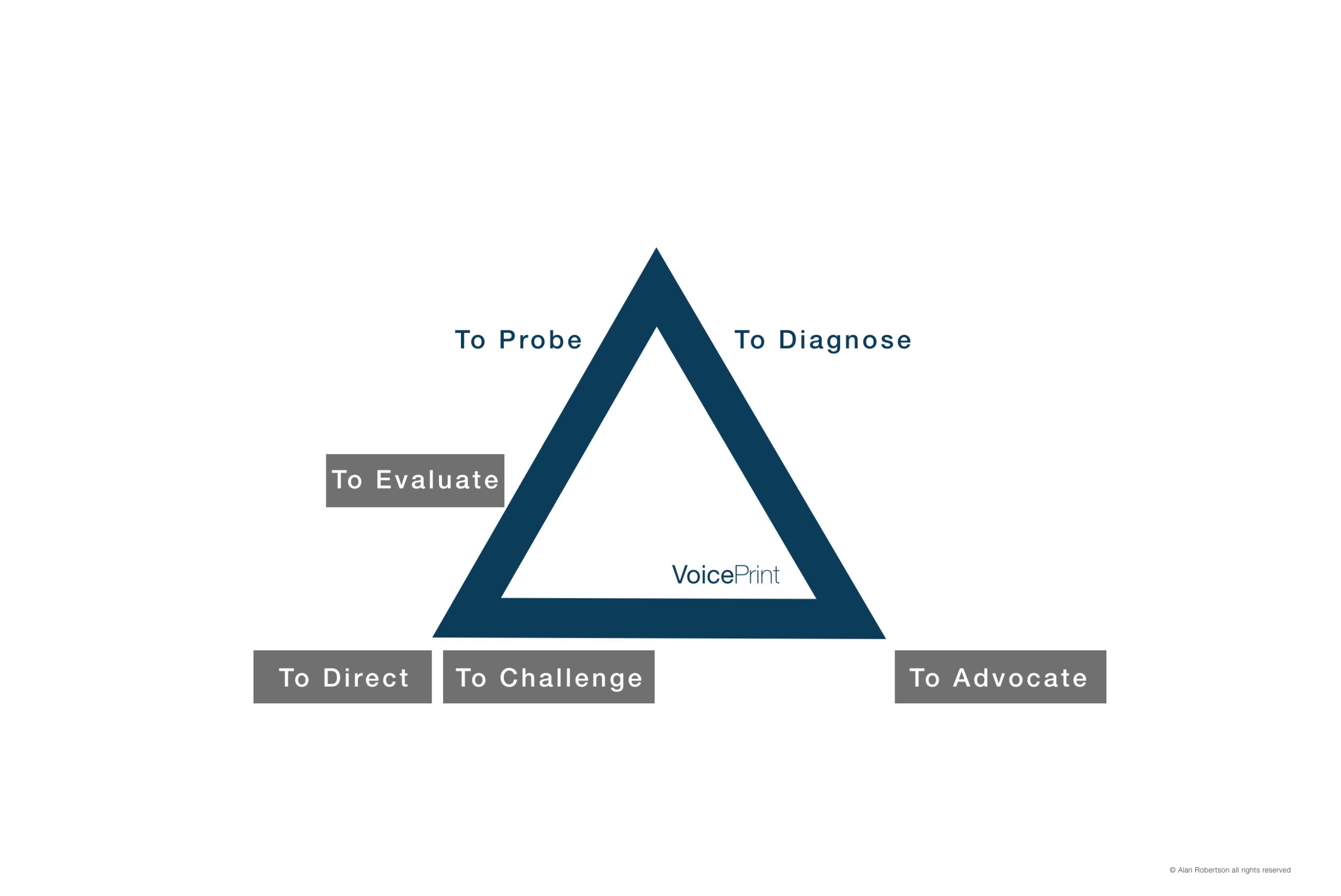

Helping him to name his feelings allowed him to realise that his outbursts were triggered, not by anger as such, but by frustration. Frustration occurs when we feel blocked, when we have a sense of what we want or what we think should be happening, but progress towards it is impeded. In terms of ‘voices,’ frustration is not likely to come out in any of the ‘exploring’ voices, since these all require a degree of patience. Nor is it likely to be expressed through the calm objectivity of the Evaluate or Articulate voices. Frustration is more likely to emerge in the form of one of the more ‘decided’ voices, especially Challenge, Advocate or Direct, or to burst out in the dysfunctional form that any of the nine voices can take when too much energy surges into it.

In Graham’s case frustration poured out along the natural contours of his personality as an extraverted thinking type. Evaluate, Challenge and Advocate were his primary voices with Direct also in the high range. His tendency to use these voices more extensively than most people increased the danger that he would be heard by others as Criticising, Attacking, Preaching or Dictating. The danger was compounded by his tendency to make disproportionate use of these voices in more pressurised circumstances. It was easy to see how Graham’s profile could have earned him a reputation for being loud, insensitive and difficult.

We needed to uncover the source of Graham’s frustrations, but the more immediate priority was to interrupt his habitual pattern. “I’m a barker, not a biter,” he insisted. That may be true, but it’s too fine a distinction to expect people to draw when they find themselves faced with a barker.

We opted for a radical change, to make Inquiry – at that stage his least-used voice – a much more prominent element in Graham’s VoicePrint. We talked at length about what this would mean in practice. Don’t be in such a rush to act. Get the other person’s perspective first. Discover what they’re concerned about. Show them you’re listening. Give them the respect of being and feeling heard. Give yourself the benefit of more information before you commit.

A radical adjustment like this was never going to be easy, but Graham had the advantage of wanting to learn, and wanting to apply what he was learning to his personal as well as his professional life. This further opportunity and incentive to practise his new voice gave his coaching an extra momentum and additional indicators of whether we were making progress. “There’s one thing I really want to achieve,” he confided. “Can you help me to stop swearing so much.”

It is a new dimension, both for me as a coach and for VoicePrint, when we start to explore the frequency, quality and occasions of Graham’s swearing. It is plentiful, colourful and seemingly spontaneous. I wonder if it is a way of adding weight or emphasis to his advocacy, but it doesn’t seem as purposeful as that. We eventually decide that it’s a crude form, both literally and metaphorically, of the Challenge voice. It’s interruptive, but it does little to re-direct or improve the quality of any dialogue. It is more probably simply another indication of how Graham bursts with energy.

So what were the sources of his blocked energy, his frustrations? The answer, as so often, proves to be complex. He gets frustrated when he feels people are not doing the best they could do. He is impatient, both by temperament and because he feels himself to be at or approaching a watershed in his career. He is ambitious. He wants to be fairly rewarded for what he feels he has contributed to growing the business into the success story that it has become. He enjoys being part of the Senior Management Team. He is open to his own career developing either in the scientific or the general management field.

The problem for Graham is not that he knows he’s blocked from achieving these ambitions. It’s a subtler, more insidious difficulty: he doesn’t know. He’s receiving mixed messages. And faced with this ambiguity and feeling uncertain, he’s responding by doing what comes most naturally to him: anticipating problems and looking to get things under control as quickly as he can, throwing his energy into his work…

…barking!

…and so falling into the all too common trap of over-using a strength to the point where it becomes a weakness.

As we explore Graham’s frustrations, he makes an immensely useful disclosure. ‘I’ve never really had any formal management training.’ Suddenly we have a new and productive channel into which we can re-direct his abundant energies, transforming negative frustrations into positive outlets for his increased awareness.

I introduce Graham to a number of frameworks: approaches to handling conflict and disagreement, situational leadership, how to give constructively critical feedback, how to work with ambiguity. Our conversations revolve around helping him to think through how he can apply these to his own role, context and team. How does he apply himself to these new techniques? Energetically, of course.

Progress over the next four months is not smooth. It was never likely to be. There are still ‘moments,’ when he misses what the other person expects of him, moments when his impact lands short or wide of his intent, moments when he feels his frustration boiling up. But what has changed is that he has become much more aware of these things. Initially this awareness comes too late, after the event, but then increasingly he finds he is catching himself in the moment, when he can use his new presence of mind to choose what he says or does next, mindfully.

* * * * *

It is six months since Graham and I had our first conversation. He is speaking, not slowly, but more thoughtfully, carefully, with greater impact. He has learned when to go fast and when to slow down.

His role is no less demanding. The business is facing big transitional challenges. It’s tiring. He needs nine hours sleep, when previously he could make do with six. But he’s sleeping well. On balance he’s energised by the demands. ‘I’m not beating myself up about things that are outside my control.’

As he brings me up to date, he swears once, very mildly, immediately catches himself and apologises. He has started to delegate more and has been pleasantly surprised to find that these things are being done ‘better and faster than I could have done them with all the other demands on my time.’ He’s acquired a more articulate and discerning sense of his own role, what to expect of his own people and how to engage with others. ‘I catch myself and re-frame things. I do a lot more inquiring.’

‘It feels good,’ he tells me. ‘I won’t say I’m happy about everything, but I’m not frustrated.’ He adds, ‘In my management career this is the most rewarding and useful piece of development I’ve ever done. You haven’t tried to change who I am, but to re-focus what I do with who I am.’ That is perhaps all that a coach can ever do, to help people to re-focus what they do with who they are.

And as for being a Rocket Man, it can only be a career, if you can do the flying without the exploding.

To find out more about using the VoicePrint diagnostic and development tool to help people become ‘Talk-Wise’ please get in touch.

Alan Robertson – business psychologist, developer of VoicePrint, Director of TalkWise Ltd

Ready for a conversation?