Catherine McIntosh is a professional mediator. She helps people to resolve their disagreements, acting as an independent third party through a process which is less formal and less expensive than resorting to litigation or going to court. Judging from the feedback she receives from her clients, she’s rather good at it. ‘Very professional.’ ‘’Very helpful.’ We felt comfortable.’ ‘This was the first time we’d been able to talk.’ ‘You made it easy to have a conversation.’ Given that emotions run high during disputes, these are significant accolades.

So how does she do it? The key lies in the process and the moments of greatest pressure from Catherine’s point of view, are not to do with the content of what is discussed, but come when she is getting the parties to understand, accept and stick to that process. As the mediator, she is not there to decide or even to advise. She’s there to manage the process, the iterative process of enabling the disputing parties to explore whether or not they are prepared to move forward and reach a settlement.

Which voices does she use in this process? How does she deploy them to facilitate a productive conversation in a high stress situation?

The Articulate voice plays a central role. It’s the clarifying, matter-of-fact voice

that’s required to explain the process to the parties before the start, and then remind them of it, during the course of the mediation. It enables her to steer the process in a neutral way. Notice the phrasing that she uses. ‘We take turns to speak.’ ‘We don’t interrupt.’ ‘We’re polite and civil to each other.’ This is the Articulate voice explaining and clarifying. The mediator cannot use a more directive voice (‘You mustn’t interrupt;’ ‘It’s not acceptable when you speak like that’), because she has no formal authority over the parties. The mediator is only there by their mutual agreement, to serve as a process facilitator.

It’s the impartiality of the Articulate voice that is crucial. It sets out the situation between the parties in an objective way. It is neutral in how it presents any propositions put forward by one party for consideration by the other, and periodically summarises any progress that is being made. ‘What I’m hearing you say is…’ More fundamentally, the skilfully used Articulate voice sets a tone of objectivity for the proceedings. It not only highlights the nature of the mediator’s role, but also encourages the disputing parties to shift into a more objective frame of mind too.

That’s not where disputants tend to start. ‘Discussions are often heated,’ says Catherine, ‘especially early on.’ The parties in dispute are usually carrying a lot of emotional load, not least because there’s often a clash of personalities behind the headline issue. ‘In my experience the vast majority of mediations involve a personality clash of some sort.’ ‘Sometimes what someone really wants is simply an apology.’ The mediator therefore has to encourage people to ‘get what matters but is still unsaid out and into the room’, because time is limited. (Most mediation sessions are only about four hours long). ‘Is there anything else that you’d like to share?’ is a question that she uses regularly.

This makes Inquiry the second key voice in the professional mediator’s repertoire.

To be effective, Inquiry has to be accompanied by good listening. ‘You have to listen a huge amount.’ ‘Open listening’ is what Catherine likes to call it. The real issues and sticking points can turn out to be ‘very different to what people say in their initial position statements.’ The mediator has to be very open-minded in her questioning and her listening. ‘If you don’t listen properly, you won’t know what voice you should be using next to move the process forward.’

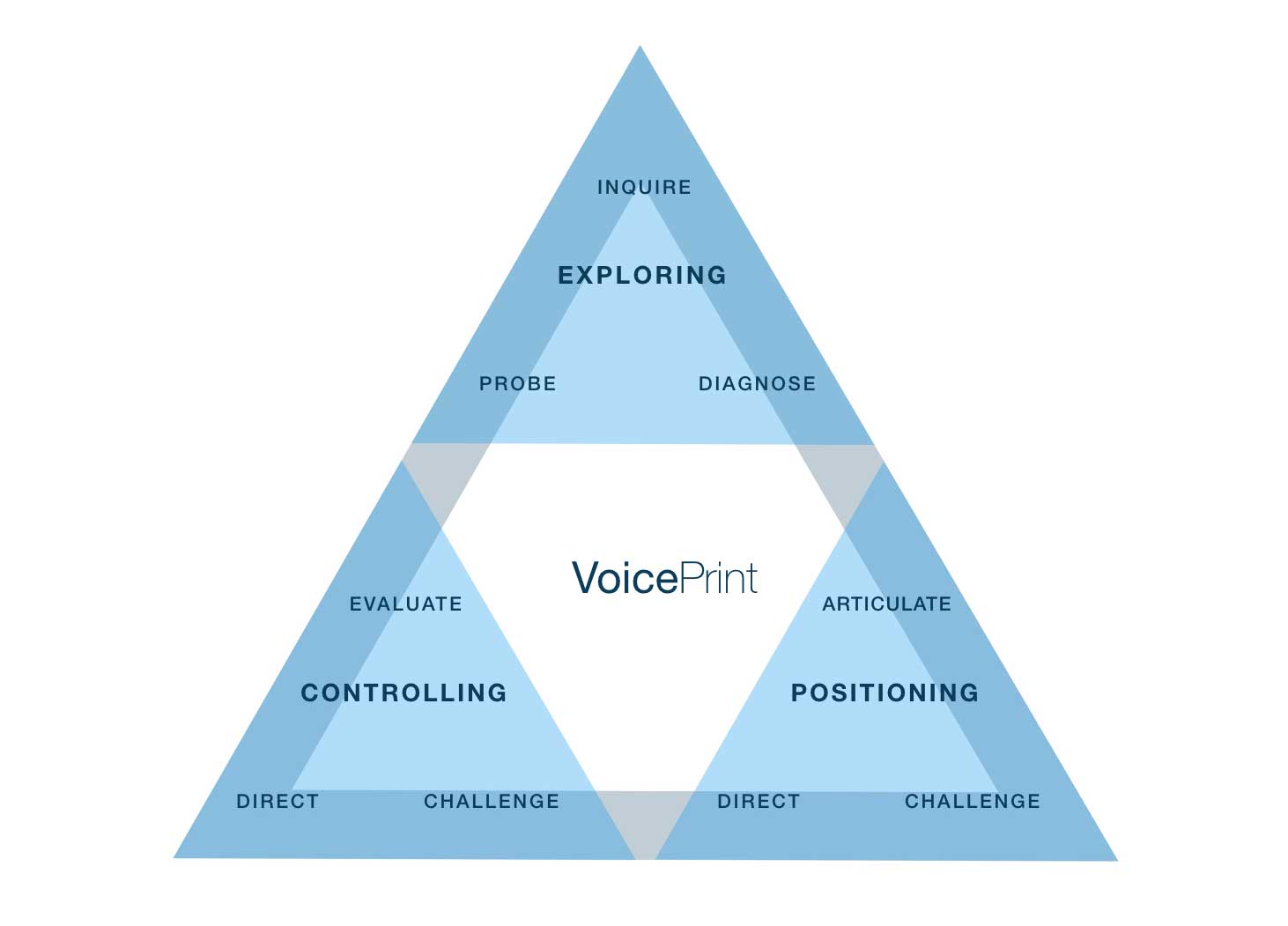

Particular care has to be taken when using the other exploring voices, because Probing can narrow the focus too much and Diagnosing can bring the mediator too close to being the one putting forward a possible solution. It’s the parties in dispute who must be prepared to suggest ways forward, and it’s noticeable that the Advise voice is not a significant part of Catherine’s VoicePrint profile.

In the same way as her Articulation can draw the parties into a more objective frame of mind, so her use of Inquiry and listening can encourage them to be more open to exploring possibilities. ‘What happens if this doesn’t settle?’ is a question that Catherine often poses to prompt the parties to re-think the implications of their positions.

The third key voice in the professional mediator’s repertoire is Evaluate.

Challenge, a more abrupt controlling voice, occasionally has its place too, especially when the disputants are both in the same room and no progress is being made, but its function is to get people to stay with the process. ‘We agreed that we’re not going to make demands, but we are going to ask questions.’ ‘We said we would not keep going back to the same point.’

Evaluation is not a re-focusing device, but a more thorough form of assessment, and it becomes more important as movements and the prospects for a settlement begin to emerge. Its purpose is to enable each party in turn to weigh up the proposition or counter-proposition that the other party is relaying to them through the mediator. (After the initial introductory expositions, usually held with all concerned in the same room, the parties withdraw to separate rooms and the mediator manages the process by shuttling between them.)

Again, the mediator’s role is not to carry out the evaluation of these proposals for her clients, but to help them to adopt and use the Evaluate voice for themselves.

It can be difficult, but at the same time particularly valuable, if they are still in the grip of strong emotions. You can see why Catherine describes her role as ‘a tough form of neutrality’, when she tells her clients, ‘It doesn’t actually matter to me what you decide. Of course I’d like you to go away happy, but the question you have to ask yourself is whether you’re satisfied to move forward on this basis.’

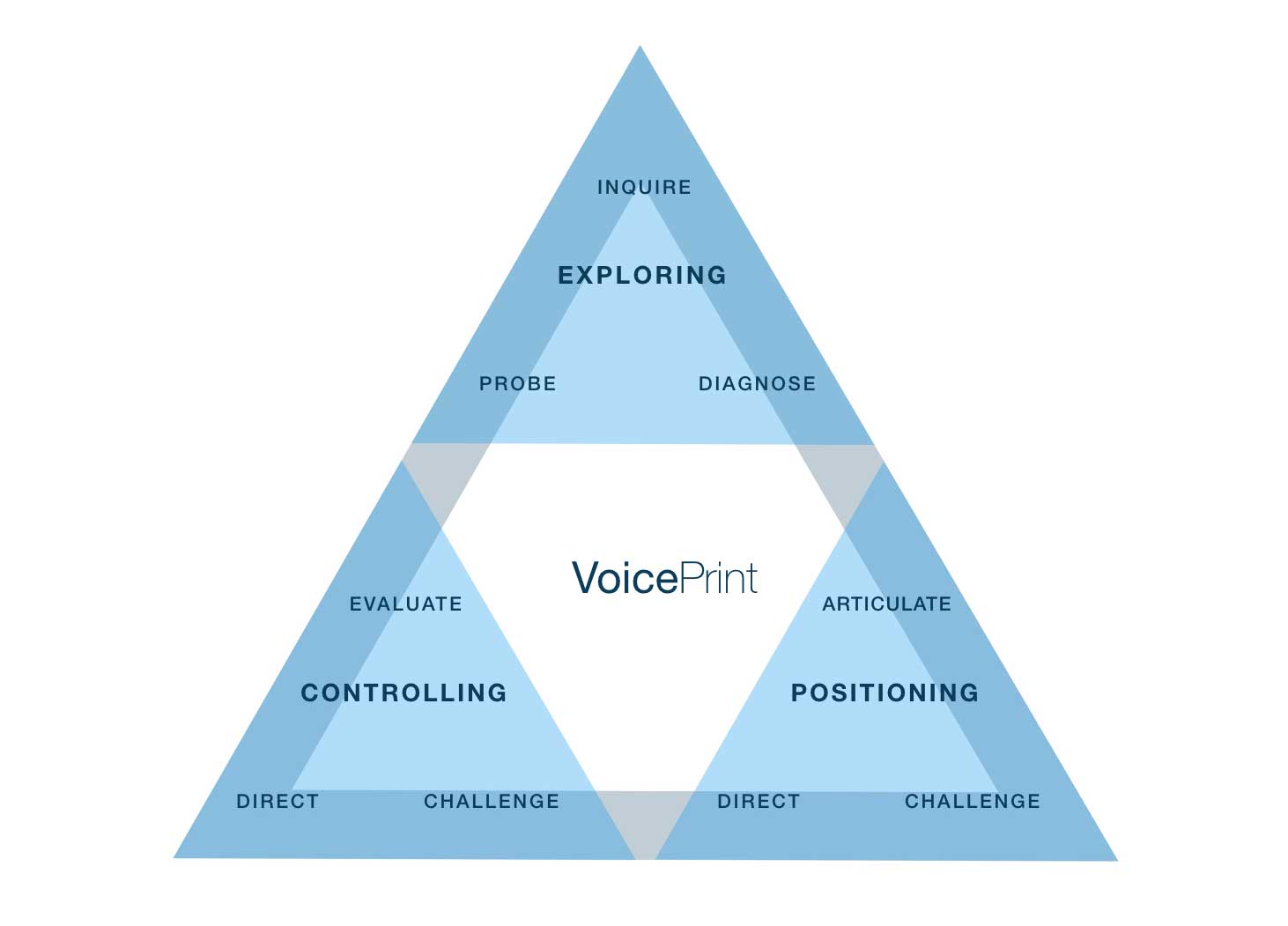

You can see what makes mediation effective, if you map the voices in the room and the changing dynamics that Catherine produces in the interaction.

The disputing parties start out using the voices that are already strongly decided: Advocating, Challenging and Directing. (‘Here’s my position.’ ‘That’s not acceptable.’ ‘What he should be doing is…’) The problem is that when both parties rely on voices that are closed and inflexible like this, then it produces stalemate very quickly.

What the mediator brings to this situation is a set of voices, which is not only more balanced, but fundamentally more open. The objectivity of the Articulate and Evaluate voices provides a bridge and the openness of Inquiry encourages the disputants to move away from where they have got themselves stuck (in the ‘red zone’) and to travel in the direction of exploring and agreeing new possibilities.

It’s a dynamic that can usefully be adopted in many other situations, where the differences of opinion might not have reached the point of needing professional mediation but would still benefit enormously from a shift into a more productive pattern of interaction.

Alan Robertson

With special thanks to Catherine McIntosh, a very skilful user of voices in her various roles as professional mediator, human resource consultant, magistrate, school governor and accredited VoicePrint practitioner.

You can contact Catherine McIntosh via http://www.mcintosh-hr.co.uk/

Ready for a conversation?