Talking Leadership:

deciding how your organisation will converse

The multi-faceted nature of its demands does much to explain why sustained, successful leadership is so elusive. Among those demands one which receives too little attention, in either theory or practice, is the leader’s responsibility for the way the organisation talks.

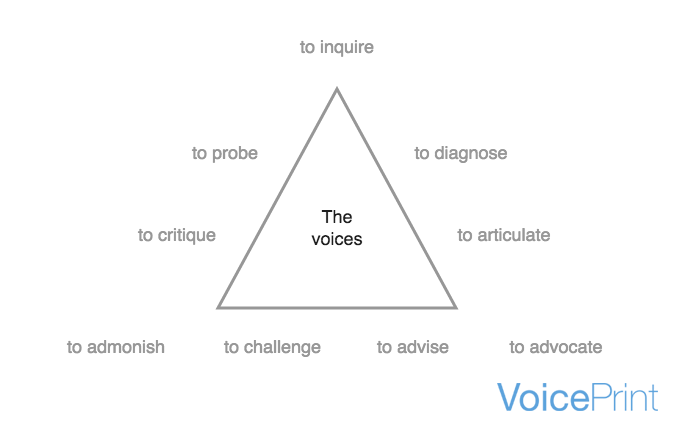

I am not referring to the content of the organisational discourse, the subject matter of its particular domain, far less the rhetoric of the campaigns, initiatives and mission statements with which it is currently preoccupied. I am talking about the ‘voices’ which the leader, either consciously or unconsciously, uses, encourages or discourages and which shape the manner and outcome of the conversations in that organisation. If organisational success is about how effectively people work together, then talk is a key variable, because talking is the primary form of organisational action; it is how people work together and get things done.

So what is the talk like in your organisation? Is it open and constructive or inhibited and conflicted? Is inquiry accompanied by careful listening or undermined by over-talking and impatience? Is criticism objective and balanced or partial and personal? Is advocacy informed and authentic or self-interested and political? What does your talk need to be like to accomplish your organisation’s objectives?

The leader’s role in answering this final question is pivotal. With regard to talk, as with so many other aspects of behaviour, people look upwards for a lead as to what is expected and acceptable and tend to behave accordingly. It is important therefore for any leader to be attentive, thoughtful and active in the shaping of how their organisation talks.

It follows that leaders need not just an understanding of, and ideally a personal fluency with, the different ‘voices’ which might be required, but also clarity about the types of conversations that people need to be having, and a sense of when and how particular combinations of voices will facilitate or hinder those conversations.

The question of what sorts of conversations the organisation needs to be having is always going to be specific to that particular organisation’s context, purpose and circumstances. It is one of the judgement calls to be considered and made. At a general level, however, it is possible to describe a typology of conversations that require leadership rather than merely management.

I draw this distinction, because while management is essentially about exercising control, about driving things towards desired outcomes, leadership is what is required when it is much less clear what should be done. Managers work with comparative clarity. Leaders, especially these days, work with ambiguity – in conditions of complexity, uncertainty and volatility. Leadership is about the movement into the unfamiliar and the unknown.

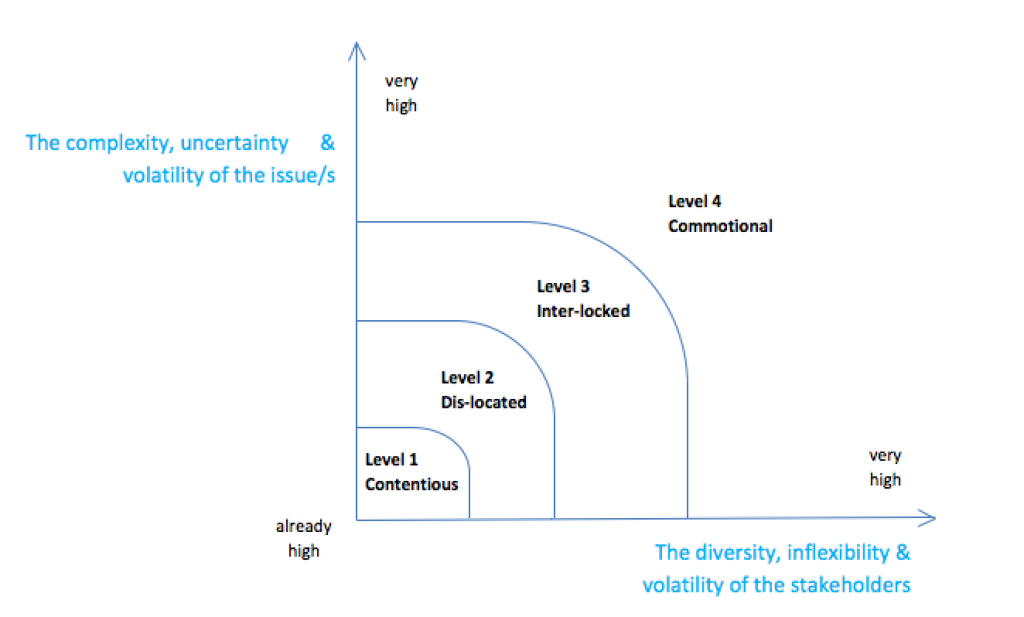

The Business Cognition leadership model distinguishes four levels of ambiguity.

Figure A: Different Levels of Ambiguity

‘Contentious’ ambiguity exists where there is a complex problem to be resolved and people are divided and in dispute over what should be done. At this first level the issue is knotty, but at least it is relatively clear what it is and who is involved. Level 2 is ‘Dislocated’ ambiguity, where the issue itself is less clear; it may be, as so many organisational challenges are, multi-dimensional, or alternatively new and still emergent, such as the implications of an irruptive technology or a legislative change. At level 3 ambiguity becomes ‘Inter-Locked’ and even harder to resolve, when the high complexity of the issue/s is exacerbated by the increased diversity of those with a significant stake in them. The range of differing perspectives, and the strength of the vested beliefs and feelings that lie behind them, combine to make productive dialogue and progress harder than ever. These difficulties are rendered even more acute in conditions of urgency, or ‘Commotional’ ambiguity, when emotions become sharper, reasoning, tolerance and learned behaviours become more fragile, and productive conversation involving all the stakeholders becomes hardest of all.

In conditions like these, where there is little agreement about the issue and less agreement about how to proceed, there are no techniques which guarantee success. There are, however, approaches which improve the odds and increase the likelihood of moving in a useful direction. In essence, these approaches are:

- To respect the ambiguity, to work with it rather than ignoring it or seeking simply (and simplistically) to dominate it;

- To work collaboratively (rather than combatively), harnessing different perspectives to the joint and creative exploration of possibilities;

- To pursue a process of iterative sense-making, progressively refining both the thinking that is being done and the actions that are being taken.

The leader’s role is not to do it all personally, but to elicit and facilitate the conversations through which individual and departmental energies and talents can be brought together in productive conversation. This entails recognising that the form of conversation most likely to be useful is subtly different for each type of ambiguity. It is more like a mediation at level 1, a fresh delineation at level 2, a progressive deliberation at level 3, and a co-generative hub at level 4. These are all forms of collaborative conversation, but the emphasis, and the accent on particular voices, varies somewhat from one to the next. Getting the balance right makes good use of energy; it saves time and resources, it reduces frustration and pressure.

So where do you stand personally? Do you know which voices and combinations of voices are necessary to create and hold each of these different types of conversation? Do you recognise which voices, while useful in the context of ‘business as usual’, might need to be tempered or contained in the context of greater ambiguity? Do you have the requisite voices in your own team? Are you confident that you can orchestrate and get the best out of them, when the discussions become emotionally charged? How does your own profile of voices shape the pattern of conversation in your organisation?

You are invited to have a think about these questions in relation to the nine voices identified in VoicePrint, the model of competent talk. If you’d also like to talk to someone about these questions, then one of our accredited coaches or consultants would be pleased to have an exploratory conversation with you and to share the insights that have been gained from our research and practice, you can get in touch with us by emailing [email protected] or connect with us on linkedin and twitter.

Author: Alan Robertson

Director Business Cognition Ltd & co-creator of VoicePrint

Ready for a conversation?